The Ploughed Fields of Agincourt.

The distinctive ridge and furrow of medieval ploughland at Cold newton, Leicestershire (Image: Matt Neale, Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cold_Newton_ridge_and_furrow.jpg).

I was reading something about medieval landscapes recently, for the course I teach on castles, and came across a description of medieval ridge-and-furrow ploughland that completely changed my mental picture of the battlefield of Agincourt, and the terrain that hampered the French knights advancing against Henry’s lines.

Medieval Ploughing and its impact on the landscape.

Most arable land was split into a series of strips, each cultivated by a separate family. Whilst exact dimensions could vary, they tended to be a ‘furlong’ in length - the distance a team of oxen could plough without being rested, or about 200 metres (650 feet) - and between four-and-a-half and twenty metres (between fifteen and sixty-five feet) wide. The strips connect often at odd angles, workgin wiht the natural topography to minimise the need to plough uphill, to maximise the amount of land put to the plough, and to distinguish one man’s strip from another.

The ploughing of these strips was done with a plough that had ploughshare (the blade) and mould-board (the piece of a plough that turns the soil). These were fixed, turning the soil over to the right of the plough as it moved through the earth. As the plough was drawn up a field strip, lifted and turned around the short ‘headland’ and back down the other side of the strip, the earth would bank up toward the centre of the strip to form a ridge, with a consequent furrow, or depression, being created between the strips. As the teams of oxen started to be turned as they reached the headland, the plough would twist, creating a distinctive reverse s-shape.

Over time the ploughing of the strip in the same direction season after season caused the ridge to build higher and higher. This was beneficial to drainage as the furrows would collect moisture (and were often planted with beans, or barley and oats, crops which benefit from wetter soil). The difference in height could be extreme, especially in heavier soils where drainage was more important. A difference of a metre (three to four feet) was common, whilst in some the top of the ridge might lie some two metres (six feet) above the base of the furrow. The fact that medieval ridge and furrow can still be seen in some modern pastures to this day, albeit a shadow of their former selves at barely a half-metre (two feet), is an indicator of just how deep these features once were.

The battlefield is still agricultural land, ploughed for the growing of cereal crops. However modern techniques will have flattened out the corrugations of ridge and furrow that the French knights would have had to cross in 1415. (https://sirgawainsworld.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/agincourt-oct-25th-2009-from-maisoncelles-towards-agincourt-left-and-tramecourt-right.jpg, accessed 21/4/24)

The ploughed field of Agincourt.

We know, from contemporary accounts, that the fields around Tramencourt and Agincourt, over which the French army advanced had recently been ploughed, and were sodden from recent heavy rains. Walsingham’s chronicle notes that the fields were newly sown with wheat, and were rough and muddy, exhausting the French marching across it, whilst the author of the contemporary French chronicle the ‘Histoire de Charles VI’ records that the ground ‘had been newly worked over, and that torrents of rain had flooded and converted into a quagmire’. Pierre Cochon, another French chronicler, says that the ground ‘was so soft that the men-at-arms sank into it by at least a foot’.

Most historians mention this as a factor in the French defeat. The boggy ground - a heavy, sticky clay - made it hard for men in full plate to advance and to fight, and those who stumbled and fell might well find themselves unable to gain purchase to stand in the morass of churned up mud. However I suspect that, like me, most of them have had an image of a modern field in mind, with ridges of broken turf capable of turning an ankle or tripping one up; difficult and tiring to walk over, for sure, but by no means impassible. Certainly most illustrations of the battle, or depictions in film, represent it as such.

A medieval ploughed field would, I suggest, have been much, much worse.

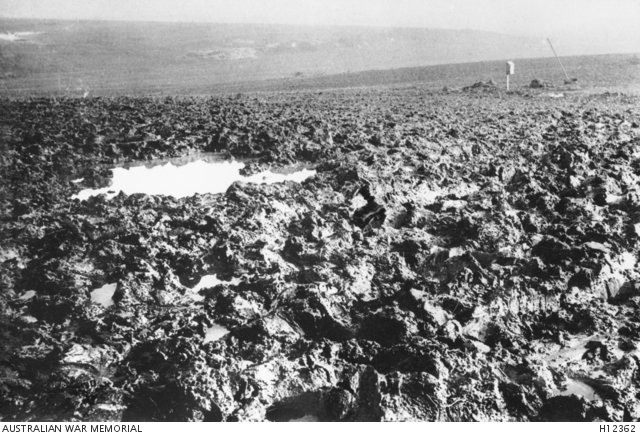

Mud is synonymous with the fighting of the battle of the Somme in 1916. Agincourt was fought over the same churned soil, barely fifty miles distant. (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/H12362, accessed 21/4/24)

Rather than just crossing ground cut up by the action of the plough, the French troops were also advancing across a landscape that was also corrugated by well-established ridges and furrows. If the battle-lines ran parallel to the course of the plough, they would have had to clamber up and down banks a metre to two metres high, dropping down the other side, and repeating that perhaps as little as every five or six metres. The banks would have been steep and slimy with plough-churned mud, whilst the bottom of each furrow would have been a ditch of mud and rainwater. If the battle-line ran perpendicular to the ridge and furrow, so that the men-at-arms advanced up their length, it would have been little better, some wading through the sodden furrows whilst others tried to keep their footing on the steep and slippery banks of the ridge.

The landscape of Agincourt might have been more reminiscent of the Somme battlefields of the First World War rather than the green open fields over which we tend to picture medieval armies fighting.

Further Reading

S. R. Eyre, ‘The Curving Plough-Strip and its Historcial Implications.’ The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1955), pp. 80-94 https://www.bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/03n2a2.pdf (accessed 21/4/24)

Imogen Clarkson Wright, ‘What is Medieval Ridge and Furrow?’ https://ruralhistoria.com/2023/10/15/medieval-ridge-and-furrow/ (accessed 21/4/24)

Anne Curry, The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations. (Woodbridge, 2000)

Oliver Rackham, The Illustrated History of the Countryside. (London, 2003)